1964

This was the year everything changed. All of the stirrings that had been building up since the switch to the new decade suddenly exploded, creating an earth-shattering neo-Big Bang of popular culture in music, that would continue to expand exponentially throughout the remainder of the decade and beyond. The early 1960s had laid the foundations: Elvis Presley’s return, Bob Dylan’s breakthrough in the new folk scene, the emergence of Motown as a commercially viable force, the exciting new hot sound of "soul," Phil Spector’s masterfully crafted "wall of sound," and that strange buildup in Great Britain that was going by the name of "Beatlemania." In the end, it was this final, confounding ingredient that suddenly, without any warning, ripped its unprecedented presence with a power that literally stunned a an unsuspecting nation. In January of 1964, it was a rumor, growing day by day, glimpsed occasionally on TV clips, then beginning to be heard on the radio. Suddenly it was in the air - it was everywhere. Even at the age of five years old, I clearly sensed the buzz, the excitement, the curiosity, the power: And I kept hearing that name. The Beatles . . .

Bang! Everything in the country seemingly changed overnight. I remember a world suddenly suffused with Beatle records, Beatle magazines, Beatle wigs, Beatle coloring books, Beatle lunchboxes, Beatle candy, Beatle everything! It was all that the kids in my class talked about - and all of our parents and teachers as well, though their reaction seemed to be one of confusion and befuddlement. Fifty years later, I remember that feeling so well, and I haven’t felt anything even remotely like it since. The Beatles changed everything. EVERYTHING! Their arrival somehow seemed bigger than the moon landing five years later, and I lived through both. Even now it’s difficult to say which event had the more lasting effect.

How can one even begin to explain the power, depth, and ultimate longevity of this phenomenon? I can’t. So many people have tried, and every one of them have ultimately fallen short of analyzing all the many forces and dynamics that were in place as the calendar switched over from 1963. Yes, things were changing, Bob Dylan was right. There was the civil rights movement, the escalating war in Viet Nam, the burgeoning explosion of the baby boomer generation. The sparkling vision of an unlimited potential for social and economic transcendence had already been dangling in the air, although side-by-side with the ultimate threat of nuclear destruction. The American nation’s destiny seemed clear and confirmed, having grown steadily since the victorious end of World War II barely 20 years before. This was a nation not only with a future, but a mission - a God-delivered mandate to change the world for good and forever. I honestly don’t believe that anything seemed more clear to almost everyone in the Western world that America was the nation of destiny that it had always felt itself to be, and that it was finally her turn to lead the world forward a new kind of life, a new kind of perfection, filled with unfailing optimism, hope, and courage for the future. And that glorious sense of limitless, fearless and the forthcoming inevitable perfectibility of man was physically embodied in our beautiful, brilliant, young president. I looked into his eyes as the motorcade passed by my school, and as we all cheered him and his magnificent first lady, there was no question in any mind present that we were standing on the precipice of destiny.

On November 22, 1963, the Beatles released their second album in Britain. Although it immediately went to the top of the pop charts, replacing their first album at the No. 1 spot, nobody even knew about it here. The only thing that we knew that day was that everything we had believed in was totally shattered. Shock, pain, confusion and fear were everywhere. And then we fell into a deep and dark abyss of gloom and despair. It was a very black Christmas. All our hopes and beliefs, our confidences and our pride had been taken from us in just a few instants. As I watched my parents and teachers cry, I remember wondering if this was truly the end of the world.

It’s an old cliche’ to say that the Beatles arrived just at the right moment to help revive the grieving spirits of a nation in mourning, and I’m not even certain that it is true. Actually, if Kennedy had still been alive and in the White House in January of 1964, I think the Beatles would have still been just as big - perhaps even bigger. But something had fundamentally changed in this country, something even larger than one human being had died that day. Or almost died. We were a nation of orphans. But, think for a moment, and imagine how it must have felt to those millions and millions of young people who had just seen their legacy shattered on a street in Dallas only one month before. What do you think they thought and they felt when they first heard the Beatles? What did that music say to them? How do you think they felt when they heard the Beatles were coming?

When the Beatles first hit American radio - and then, about a month later, American shores - American youth heard something that perhaps they had thought they would never hear again. They heard hope. They heard joy. They heard the unlimited sound of infinite possibilities. They heard the future. And by God, they were ready to rise up and live again!

Well, that’s one interpretation anyway. That’s what it felt like to me, and mythically speaking, that’s the way it seems looking back. And incredibly enough, that was the dynamic that played out for that whole generation of Americans throughout that decade and beyond. If our political and social ideals had been shattered, and while we watched as each year ticked on and the old establishment politicians and money-men were determined to drag us deeper and deeper into a mire of disillusion and defeat, we were going to fight back. And we would follow the ones that first gave us that promise of new life - we would follow the Beatles. And miraculously, they never, ever let us down. We grew into a new nation together - a trans-boundaried nation of hungry, idealistic youth.

The most astonishing thing, really, is that the Beatles were actually up to the job! They really were that good - just go back and listen to them. Oh, right, you still do. So do your kids. So, seemingly, will their kids. And as the Beatles matured, we matured. They affected everything around them, and soon America and Europe were flourishing with new forms of music, of dress, of hair, of politics, of morals, of spirituality - of everything! And the Beatles were up to it - they reacted to the change and always took us one step ahead to the next level. But I’m getting ahead of the story . . .

All throughout 1963, while the Beatles were tearing up the charts at home, they couldn’t get a record played on American radio. Their U.S. distributor, Capitol Records, had so little faith in the group’s prospects in America that they refused to issue their singles - so EMI, the Beatles’ British powerhouse corporation, contracted with little labels like Vee-Jay and Swan. No action. Nothing. Zip.

Then all of a sudden in mid-December, a handful of American disc jockeys began promoting their records in different independent markets. Word started to spread. By the first week of January, the Beatles were being played in New York City. Capitol finally got on the bandwagon and hurriedly released their latest British single, "I Want to Hold Your Hand" on December 26, 1963. The group quickly spread like wildfire on radios throughout the entire country, and stations were swamped with requests. Soon, just about every other song that played on American dials were the Beatles. Swan’s recording of their previous hit, "She Loves You," (which could get no airplay when it was initially released back in September) with its insanely infectious "Yeah, yeah, yeah!" refrain took off right behind it. Vee-Jay re-released their Beatles singles and quickly prepared the first American album, Introducing . . . The Beatles, for release by January 10. It really happened all that fast. By February 1, "I Want to Hold Your Hand" held the No. 1 spot in the American charts. "She Loves You" held at the No. 2 spot for five weeks until it finally replaced "Hand" at the top spot. And finally, on April 4, 1964, the Beatles became the first and only artists ever to hold all top five positions on the American pop chart. Beatlemania was an inconceivable phenomenon that absolutely devoured the nation.

Everybody knows all this, but I think it’s important to remind people that it actually happened - and how unbelievably extraordinary it was. For those who weren’t alive, it’s impossible to communicate the sheer level of excitement that went with it. And of course, this wasn’t just a big break for the Beatles. 1964 would see the dawn of "The British Invasion" as the Rolling Stones, the Animals, the Dave Clark Five, the Kinks, Gerry & the Pacemakers, Dusty Springfield, Herman’s Hermits, the Hollies, the Zombies, Peter & Gordon, Manfred Mann and countless others would all have hits in America. It was truly the beginning of a new era - something as unprecedented and exciting as the birth of rock ‘n’ roll itself some ten years earlier.

As for the Beatles, America’s perception of them was totally cramped and distorted. The British public had already experienced a full year of Beatle madness, and during that time, the group had recorded and released two full albums, plus five hit singles. To the American eye, this group had simply materialized out of nowhere and had seemingly an endless supply of great material that they just magically pulled out of a hat. All that long year’s worth of work hit America at once! This was just too much to take in, too much to wrap one’s brain around. And Capitol discovered that they could maximize their profits by cutting up the group’s albums, whittling them down to 11 or 12 instead of 14 songs, stick the singles (both A-sides and B-sides) judiciously on the LPs (which the group had kept strictly separate in the UK), both to boost the amount of product and to force the kids to pay twice for the same songs. In 1964, the Beatles would release two new albums, one separate EP of four new songs and three singles in the U.K. In America, seven Beatles albums and over ten singles (excluding 1963’s "I Want to Hold Your Hand" and "She Loves You") would appear. Not only did this give American audiences a sense of sheer overwhelmment, but it would badly present a garbled, confused and essentially false sense of the band’s development. Unfortunately, Capitol would keep up these kinds of practices for three years, until finally, with the 1967 release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Beatles would put their collective feet down and demand that their American and British products matched one another. (It took until the 1980s, and the CD era before the American audience would get all of the Beatles releases properly sorted out!)

In the coming pages, I will concentrate on the Beatles original U.K. releases as their proper canonical recordings, but I will also list the American releases so that readers can get an historically valid picture of just how the Beatles’ material was initially entered into the mainstream of U.S. culture. (I will also do this for the Rolling Stones, and periodically, for other British artists as well.)

All that being said, believe it or not, there was much more than the Beatles (or even the British Invasion) to popular music in 1964. But the Beatles carried the banner of the new era, and everything that followed - all the way throughout the rest of the 1960s - would seem to follow in their wake.

Otis Redding: Pain in My Heart

(January 1, 1964)

Soul. One of the most powerful and directly affecting forms of music of the 1960s had its roots deep in the blues, as well as in the frenzy of the black gospel church. It’s difficult to nail down precisely when and how "soul" emerged as a separate musical genre, but we can clearly see its beginnings in a new sound in R&B records by James Brown and Ray Charles in the mid-to-late 1950s. However, in many ways, the young Otis Ray Redding, Jr. embodied the form’s purest expression. For as exciting and dynamic as James Brown was, he always seemed to have at least one foot pushing in the future, traveling to someplace new and astonishing. When Otis arrived on the scene, he more or less took up the place that James Brown was vacating, and he pushed it - taking it just about as far as it could conceivably go.

Although most African-American popular music of the ‘60s was called "soul music" at the time, looking back, it’s not hard to distinguish the hard, gritty, cathartic energy of an artist like Otis from the poppier (though soul-ful) songs represented by Motown and others. Soul came from the church, and it was devoted to testifying, proclaiming, shouting, reveling in joy, burning in agony and spreading the spirit in a secular context. As embodied in Otis Redding, this sound developed into one of the most powerful vehicles of transcendent deliverance that modern music could offer. Otis grabbed you in your gut, made you feel, and no matter how much pain was being expressed, he delivered a joyous sense of release to the listener, especially when he was covered in sweat and glory on the stage. He had it: His voice (and frame) was enormous. His physical presence, his mastery of timing, pronunciation, and his uncanny ability to control emotional levels let him hold audiences in the palm of his hand. He was the king of the "slow-burn": the songs that would start out small and sad, gradually building over time and rumination, until the fireworks set off at the end, a full-blown explosion that transformed tortured pain into the mightiest expression of salvation and bliss.

Otis Redding’s records sometimes caught at least almost the full glory of the man, and the best of them are masterpieces. Pain in My Heart was Otis Redding’s first album, and it caught the young singer (he was 22 at its release) in the process of emerging into what would quickly become his mature style. The debut album featured three Top 40 R&B hits that the singer had recorded for Memphis-based Stax Records over 1962-1963. The Stax/Volt sound was unique, a hard-core vision of unrestrained passion that simmered in the red-hot sauces of the American south. The house band, the legendary Booker T. and the M.G.s, pioneered tight, yet deadly funky backdrops over which singers could deliver their messages, and Redding’s blend with the group would take soul to extraordinary new heights.

The first single, "These Arms of Mine" had been recorded almost by accident, as Redding had only driven to the studio to deliver a friend to a recording session. Since they finished early, Otis got the opportunity to record two of his own songs with the band: "Hey Hey Baby" and "These Arms of Mine". Stax co-founder James Stewart was so impressed that he signed Redding to a contract, released the results as a single, and the singer eventually became the label’s biggest-selling star. In October 1962, "These Arms of Mine" appeared on Stax’s Volt label, and by the following March, it reached the No. 20 spot on Billboard’s R&B chart, and even cracked the Top 100 Pop Chart, reaching No. 85. The record went on to sell over 800,000 copies.

A second single on Volt ensued in 1963. "That’s What My Heart Needs" was another original ballad of pleading, and it topped its predecessor in both power and subtlety. Redding’s third single was his most successful yet, both artistically and commercially. Released in late 1963, Redding’s version of Naomi Neville’s "Pain in My Heart" (a "rewrite" of "Ruler of My Heart" by Irma Thomas) hit No. 11 on the R&B chart and returned the singer to the Hot 100 at No. 61.

At this point, it was decided that it was time for the Otis’ first LP, which was released on the Atco label (Atlantic Records was handling the national distribution for Stax), and it was titled after this most recent hit. It included all three singles, plus two of the B-sides, including "Pain in My Heart’s companion, the buoyant original, "Something Is Worrying Me." A fourth single from the album, called "Security," was released in April of 1964. It reached No. 23 on the R&B chart and No. 97 on the Pop Chart.

To complete the album, Redding quickly recorded six cover songs of varying quality, but Otis sounds genuinely inspired on all of them, and the band is tremendous. Although Pain in My Heart is not on level of future Redding masterpieces like 1965’s Otis Blue, this debut still stands as a solid declaration of the southern soul aesthetic and introduces the world to one of its greatest masters.

The singles are all essential, the two B-sides are highly recommended. But any true Otis Redding fan is going to want the whole package.

Side One

1. "Pain in My Heart" (Naomi Neville) - Yes, it’s a rip-off of Irma Thomas’ gorgeous "Ruler of My Heart," but at the same time it’s an entirely different animal. While Thomas’ single slinks through the sadness with the smooth sound of her expressively deep barroom baritone gliding through a mist of strings, Otis sounds like a desperate farm boy groveling in the dirt. And the instrumentation just comes from a different world. While the plunky, four-square piano pounding sounds disarmingly amateurish, the long, drawn out horns, the almost-too-slow drum-backbeat and the funky grits-and-gravy guitar of the great Steve Cropper places this song on another map entirely. And then there’s Otis. The man is in pain. There’s so much emotion in his gruff but beautifully nuanced voice, the emotion of holding back the hurt, the extraordinary ability to communicate the way controlled desperation actually feels.

There’s not much going on musically, but the sound is lonely, and the dragging repetition gives Redding the perfect platform from which to emote. Then, suddenly, during the stop-and-start bridge, he can hold back no longer, and all that passion inside flies out, far beyond his ability to keep those feelings in check: "Come back! Come back! Come back! Baby!" His begging sounds so real, the anguished cries of a vanquished, desolate, utterly conquered soul. But all that he can call back are the musicians, who’ll support him in his misery for the two full minutes of the song. This is mastery - and if it doesn’t move you way down deep where things actually hurt, you just may be dead, my friend. Catharsis with a capital C. "Someone stop this pain . . . someone stop this pain . . ."

2. "The Dog" (Rufus Thomas) - This cover is a funky workout, but is arguably not as soulful as Rufus’ slower original. It has a nice sax solo, though.

3. "Stand By Me" (Ben E. King, Jerry Lieber, Mike Stoller) - Ben E. King’s 1961 classic is the definitive version, but Redding’s looser, grittier and more existential rendering is fascinating and moving.

4. "Hey Hey Baby" (Otis Redding) - This is a rock ‘n’ roll rave-up a la Little Richard, whose vocal style Redding immediately recalls. But the record is not as pounding as Richard’s work, with a more subtle country bounce that’s amplified in Steve Cropper’s tasty guitar solo. Instead of just screaming and declaiming, Redding sets into the groove and his inspired quavers add a whole new dimension to having the hots.

5. "You Send Me" (Sam Cooke) - Cooke’s classic hit is slowed down and opened up for more dramatic impact. Redding’s deeply emotive interpretation is revelatory, almost turning the song into an entirely different listening experience. It’s perfect for slow-dancing as well.

6. "I Need Your Lovin’" (Don Gardner, Clarence Lewis, James McDougal, Bobby Robinson) - I wish I knew the background of this number. Four composers are listed, but the song just sounds like Redding’s huge voice riffing over his band’s comping - but wow, does it cook! "Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa!" This is some mighty southern soul testifying, and it’s a great way to end the first side of the album. It stops flat in the middle, then starts itself up again - a great showbiz gambit.

Side Two

7. "These Arms of Mine" (Redding) - This was Redding’s first single with Stax, originally released in 1962. While there’s nothing revolutionary about the song itself - a standard doo-wop-styled ballad tied to a pounding piano - the vocal is revelatory. Redding’s voice is big and gruff, but it combines the finesse and interiority of Sam Cooke to produce a shockingly new, honest and painful sound.

After two verses, Redding heads into the bridge where his singing becomes a cross between preaching and pleading - the astounding sound of an artist in complete control of expressing the act of falling apart. Rather than returning to the verse, the record simply fades out as the bridge repeats, seemingly endlessly, leaving the singer forever in hopeless suffering. It’s an impressive start to a great career.

8. "Louie Louie (Richard Berry) - This cover is silly but fun, adding a solid southern soul kick to the garage-rock monster. They were obviously grasping at straws to finish out the length of an album here - it probably only took one take, but it sounds great.

9. "Something Is Worrying Me" (Redding, Phil Walden) - Redding’s originals are the outstanding tracks on the album, as they seem to exist in a new world all of their own, rather than mutating something old. That holds true for this upbeat, mid-tempo song of paranoia that was the B-side to "Pain in My Heart." It’s a simple two-chord vamp with a bridge, but it’s got a killer beat, great horns, and it sounds real.

10. "Security" (Redding) - This became Redding’s fourth Stax single. Another new original, it’s a hard-core soulful rocker that fully demonstrates the kind of excitement that the man could deliver with this magical blend of musicians. It also had more substance than some of the other early songs, with a nicely developed horn arrangement, hard, driving drums and Cropper’s hot guitar licks. It’s Redding’s declamations that drive it, though, pushing it forward with those hard demands that ultimately reveal vulnerability.

11. "That’s What My Heart Need" (Redding) - Redding’s second single is a prime early example of his "slow-burn" style. Another slow and sad ballad, Otis begs and pleads, but tries hard to hold back his anguish. At the end of every verse, there is a brief halt, while Cropper adds a little repeating guitar lick to push him back before he goes too far. Each verse builds a little in emotion, until by the fourth, the singer cannot contain himself any longer, and screams out desperately with all the lung power at his disposal. "Come on and love me, baby!" How can she not - especially with those horns?

12. "Lucille" (Al Collins, Richard Penniman) - The album ends with this tremendous Little Richard cover that reveals just how much Redding’s style is indebted to the great rock ‘n’ roller. But this version is slower and looser than Richard’s, with a country-flavored feel that conjures up the delight of home cooking just as much as the lure of lust. This man savors his meat!

Musicians:

Otis Redding - vocals

Booker T. Jones - keyboards, organ, piano

Isaac Hayes - keyboards, piano

Steve Cropper - guitar, piano

Donald Dunn - bass

Al Jackson, Jr. - drums

Johnny Jenkins - guitar

Lewis Steinberg - bass

Charles Axton - tenor sax

Floyd Newman - baritone sax

Wayne Jackson - trumpet

The Beatles: "Please Please Me" /

"From Me to You" (US: January 3, 1964)

What a difference a year can make. Feeling the inevitable energy rising around them, Vee-Jay hurriedly made a new pressing of "Please Please Me," and just to be on the (greedy) safe side, backed it this time with "From Me to You." Released on the third day of the year, the double-sided hit joined both "I Want to Hold Your Hand" (on Capitol) and "She Loves You" (on the Swan label) for an extraordinary outburst of Beatles songs that would build to an unprecedented crescendo throughout the month, as the well as the months ahead. While Britons had enjoyed an entire year of succeeding Beatles releases, tracking the development and rise of this extraordinary new pop phenomenon, in America, it all hit at once! Suddenly, out of nowhere, four of the Beatles’ five first singles materialized on the radio, amazing and astounding young listeners across the country. It was unmistakably the sound of a revolution, and DJs competed with each other to see who could play the records the most. As for the kids, they couldn’t get enough.

It is literally impossible to communicate the intensity, passion and force that of all these songs made as they came crashing into the American consciousness. This was something absolutely new, endlessly exciting and undeniably revolutionary. It was a nation gripped in an unprecedented state of united euphoria. Nothing like - not even Elvis - had ever happened before, or would ever happen again.

By March, "Please Please Me" had peaked at the No. 3 spot on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. At No. 1 and No. 2 were "I Want to Hold Your Hand" and "She Loves You," respectively. Wow.

The Beatles: Introducing . . . The Beatles

(US: January 10, 1964/Revised Version: February 10, 1964)

This was the first Beatles album released in the U.S.A. Chicago’s Vee-Jay Records had purchased the rights to the group’s first UK album, Please Please Me, but they had never gotten around to actually releasing it. As Beatlemania in America built, the company quickly paid off some debts, cut a couple of songs, and rush-released the truncated LP into production just in time for the first wave to pass through and lift it to glory. Since the company had released "Please Please Me" and "Ask Me Why" as a single, they cut the original down to 12 songs from the original 14, and gave it a new name and cover photo. Since Capitol, EMI’s subsidiary in America, did not have access to the album for the rest of 1964, the lucky little label sold over a million copies of this now-collectible U.S. debut.

Not that things went all that smoothly, however. Capitol Records, in a frenzy, realized that they owned the publishing rights to "Love Me Do" and "P.S. I Love You," the group’s first UK single that was included on the album, so they decided to sue. Production was halted, the two songs were deleted, and "Please Please Me" and "Ask Me Why" were replaced. The new version was re-released a month to the day later. Whew.

Needless to say, Introducing. . . The Beatles is no longer available today in any format. But if you ever come across a 50-year-old copy at a garage sale . . . snap it up!

Bob Dylan:

The Times They Are a-Changin'

(January 13, 1964)

People who said (or still say) that Bob Dylan’s third album fails to live up to his previous masterpiece, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) are missing the whole point. No, it doesn’t have the variety and humor of that breakthrough classic. But The Time’s They Are a-Changin’ is the perfect album for its moment, incredibly coming out at almost the precise minute that what the record said - and the way it said it - hit home with such a breathtaking punch that it figuratively knocked the wind out of the collective breath of its society.

Dylan couldn’t have predicted many of the key events that would make his album absolutely relevant for the time. When he recorded these new songs from August to October of 1963, John F. Kennedy was alive and in the White House and nobody in America had ever even heard of the Beatles. Everything was different now. All one can say is that the young songwriter was so tuned in to the shifting fabric of his times that he absolutely nailed everything into place at once - and that was just on the title song. The arrival of this album at the beginning of 1964 forever changed the world’s perception of Bob Dylan. Before The Times, Dylan was a folk-prodigy wunderkid. The moment this record appeared, he was a prophet for his age.

The theme of the album was, of course, social change - radical social change. It was a call to wake up to the strange realities that everywhere were re-shaping the nation. Naturally, the Civil Rights Movement, as depicted in the title song, "Only a Pawn in Their Game," and most achingly real in "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" was an obvious presence. But that element was certainly there in "Blowin’ in the Wind" and "Oxford Town" on Freewheelin’. But the feeling was different there - it was more a sense of quizzical discomfort. Even the apocalyptic vision of "It’s a Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall" had a shimmer of innocence about it - as if the young singer had just stumbled upon a world of shocking injustice.

This record was different. It was the statement of angry, sick and defiant youth that had been forced to grow up too fast. "And I’ll know my song well before I start singing," Dylan had proclaimed on his previous album. Now he knew it too well - and it was ugly, dark and bleak.

This was a stark album for a denuded world that was heading somewhere, but it didn’t know where. If "Blowing in the Wind" was the sad sage wondering if an old world would ever change, "The Times They Are a-Changin’" were the stern warnings of the man who has been visited by God almighty and been told that the kingdom was come. These were haunted visions of suffering and injustice, told with the mournful sadness of a solitary soul who has seen too much, too soon. It’s one of Dylan’s hardest, most uncompromising albums, and listening to it today can send shivers down the spine some 50 years on. Just imagine how it felt in 1964 . . .

All songs written by Bob Dylan.

SIDE ONE

1. "The Times They Are a-Changin'" - The opening title song serves both as an overture to an album-long suite of some hard looks at reality - both socially and personally - and as a self-conscious anthem of the moment. It hits hard and square on the mark, with a melody and a voice that is at the same time somber and revelatory. This is an almost impossibly classic song that will somehow manage to stay absolutely relevant for eternity. For while it speaks directly to its moment in time, unavoidably pointing back to it, it manages to simultaneously point forward - change is the one constant in the world. Still, there is something that is so precise, so transcendently and undeniably right about the time of the song’s appearance that it gives one the shivers. "And keep your eyes wide/The chance won’t come again" is just one of the defining lines that nails the song directly to early 1964, yet remains flapping in the breeze, equally true for every moment to come.

The song features five stanzas, each of equal weight, yet somehow they build, one upon the other, until by the end, the singer’s observations are undeniable. The words are tight, sharp, and honed to the point. There isn’t a wasted syllable. Everything there is absolutely necessary and precisely in its perfect place.

Each stanza is memorable for its own particular reason, as well as its contribution to the whole. The opening "Come gather ‘round people wherever you roam/And admit that the waters around you have grown" still shocks like a wake-up call. This is indeed a new and different kind of song, but it speaks with the authority of the ages. "Then you’d better start swimming or you’ll sink like a stone" could not be uttered with more conviction. The man has your attention - and you’d better listen to him.

"Come senators, congressmen, please heed the call / Don’t stand in the doorway, don’t block up the hall" is a literal reference to the actions of reactionary southern politicians trying to prevent integration. But at the same time, it is a constant warning, both to elected officials and their constituents, that the role of leaders is to lead forward with a vision. It embodies the essential truth of the vision that conservatism is always inherently doomed, by its very nature, to harm the natural flow of history. The demand to get out in front or get out of the way remains a universal constant, no matter what the current political situation. As Heraclitus might say, nothing is permanent but change.

Perhaps the song’s most seemingly time-bound verse is its most enduringly poignant monument:

Come mothers and father throughout the land,

And don’t criticize what you can’t understand.

Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command,

Your old road is rapidly agin’ . . .

Here, Dylan seems not only to predict, but to actually inaugurate the beginning of the counter-culture. But as the years have passed, and those children have faced the ever-challenging face of parenthood, the power of those words have resonated more and more strongly with a truth and an irony that could not have been foreseen back when it was first written. For when Bob Dylan takes the stage and performs the song again today - which he does - he is an old man looking out over an ever-new generation, coming along eternally, challenging every ideal he has ever held, every certainty he has ever known. It must be a strange and profound realization that the one certainty he can hold onto is the one that ever faces him in a state of constant challenge.

The song ends with a Biblical message: "And the first one now will later be last." It is the thunderous voice of authority, a true-ism that goes back to the moment when Christ pronounced it over 2000 years ago. It is a fitting ending that lifts the song onto an entirely other level of eternal wisdom and authority.

The song remains one of Dylan’s greatest and most important, and helped to solidify his reputation as a walking, breathing icon and as the undisputed leader of the new folk music movement. Rolling Stone magazine ranked it at No. 59 on their list of The 500 Greatest Songs of all time. (There are a lot of Dylan songs on that list.)

2. "Ballad of Hollis Willis" - As Dylan continued to write constantly during this period, he got into a habit of simply taking stories directly from newspapers and other media and crafting ballads around them that could stand alongside the timeless folk songs of Appalachia (and elsewhere) that had been around for a hundred years or more. There are several examples of this approach on the album, but "Hollis Willis" is perhaps the most relentless, horrifying narratives you will find sung anywhere, and the strange, angry distance of Dylan’s performance nails it into your soul. Much of the song’s power comes from its sheer simplicity. It’s a basic 12-bar blues, with Dylan picking one single chord over and over. The result is a kind of pathological, driving power that seems to both reflect the mind of the subject and serve to drive him on to his sorrowful doom. Once again, the story is simple - a South Dakota farmer has experienced such hard luck that his family is on the verge of starvation. Dylan’s second-person, present-tense narrative makes the tale close and immediate. Dylan plays and sings with restraint, trusting in the song to deliver the powerful message - he has learned much about the power of holding back to increase intensity in the two short years since his debut album. As "Hollis Brown" winds on in its cruel inevitability, the listener becomes absolutely hypnotized by its terrifying power.

"Hollis Brown" is a portrait of madness, but it’s a madness that is all too rooted in a reality that holds its own logic firmly in view. What is the rational response to a baby’s tears from hunger, another day without relief in sight? But finally, the great tragedy of "Hollis Brown" is the character’s palpable aloneness. This is happening now, here, anywhere, and we are hearing about it as it develops. Yet no one reaches out, no one helps. We are all isolated in this hopeless, deserted world that must, yes has to change. As Hollis Brown finally, quietly shoots his family and himself down, we are all complicit. Dylan’s final line could either represent hope or surrender: "Somewhere in the distance there’s seven new people born." Their destiny may ultimately lie with us.

3. "With God on Our Side" - This slow, ponderous 7-minute track is nothing less than a revisionist view of history, spanning two centuries of American military engagements, from the white conquest of the Native Americans up to the present-day Cold War. There are nine verses detailing conquests, each of them with the conviction that the nation was fighting with the blessings of the Almighty. This arrogant assumption is only implicitly called into question, as Dylan claims he was taught, and "learned to accept" the obvious verity of this point of view. By not directly challenging each example, Dylan slowly builds up his argument against such presumption. Observations such as the vague purpose of the First World War resonate with the acceptance that the American consciousness is supposed to unquestioningly accept the righteousness of their government’s military actions. It is with strange fascination that when we listen to this song, we recall that this was basically the unquestioned perspective of the national consciousness up until the Viet Nam conflicts of the 1960s. While the blunt power of Dylan’s message is lost to us in our more self-critical age, it is astonishing to think of a 1964 listener’s criticism of such the unquestioned "righteousness" of such pointless outrages throughout history. Many young people had their eyes opened wide by this song, and it is not too much of a stretch of the imagination that it effect had the power to sink into the popular consciousness over the next few years. Sometimes in a great while a song, a poem, a movie - in short, a work of art - can help trigger the re-examination of basic cultural assumptions and go on to actually help change the world. Amazingly, this is precisely what happened here. And that is something extraordinary, to say the least.

4. "One Too Many Mornings" - This short, quiet, reflective ballad features one of Dylan’s most lovely melodies to date, and his delivery is soft, gentle and extraordinarily touching. Apparently, it is a rumination on a failed relationship, but instead of describing the circumstances, Dylan gently paints images of loneliness in his immediate surroundings. This song paints a kind of sadness and regret that rings eternally. The repeated phrase, "One too many mornings an’ a thousand miles behind" seems to defy exact exposition, but it indelibly leaves its impression of something beautiful that was just missed by a mark, but is now lost forever. "You’re right from your side/I’m right from mine" is a wise observation of how some small human tragedies can neither be condemned nor avoided. This is a true poet’s song, and it is a great one.

5. "North Country Blues" - The final song on Side One retreats from personal concerns to tell the long, sad story of the gradual disintegration of a small mining town, as narrated by a woman whose life is intertwined with it. Obviously modeled on similar folk ballads, the song gains resonance when one realizes that this story comes from the red mining country of Bob Dylan’s youth, the desolate coal country of Minnesota. Absolutely hypnotic in its effect, the narration of "North Country Blues" eschews any histrionics and allows the heroine to quietly paint her lost and broken life in simple reportage. Decades of disease, disaster and death pile up, hard times turn to hopelessness as mines are shut down, families fall apart, and the song ends with no future for the singer or her children. Dylan’s extraordinary gift of quiet empathy shames us into thinking that such hard times not only go on, but continually go on, with no one watching or helping entire communities of doomed souls. This pervading sense of "aloneness," as it is implied by its context on the album, is yet another thing that must change in the times to come. Simple and direct, "North Country" is both compelling and difficult to listen to. It not only inspires empathy but a difficult-to-define sense of collective guilt.

SIDE TWO

6. "Only a Pawn in Their Game" - On June 12, 1963, African-American Civil Rights activist Medgar Evers was shot dead in his driveway in Mississippi by a white supremacist who escaped justice for over 30 years. Dylan’s song is not merely a tribute to Evers, his sacrifice and his bravery. It is a stunning, biting, critical analysis of the dynamics of Southern racism in the United States. Dylan takes the blame from the shooter and instead places it squarely on the shoulders of the privileged wealthy elite and the corrupt politicians whose goal is to brainwash and manipulate the poor whites of the region. Their twisted evil reasoning fades to a devastating transparency as Dylan unveils their cynical rationale through the verses. As long as the poor whites are convinced that they are "better" than the blacks, they will side with their oppressors, swallow their propaganda, and ultimately function as vicious caretakers of the economically depraved state of their social order. It is a visionary, deep-seeing song that looks beyond the obvious finger-pointing to reveal the deep inner corruption that the mainstream media will not reveal. Just as "Masters of War" pointed beyond conventional political war-mongering to reveal the hidden profit motive that drives international conflicts, "Only a Pawn" reveals Dylan as a far-sighted visionary that can see through people’s hidden motives.

The lyrics are not only revelatory, but the structure of the song itself is designed to bore down into the listener’s consciousness, beginning broadly, then tightening up with ever-shorter, ever-sharper lines that drive the singer’s point home. Here, Dylan doesn’t have to preach. Here, he is merely a reporter, and the facts tell the story for him. Whether the song changed any white bigot’s perspective is unknown but fairly unlikely. Dylan’s strategy during this period seems to be to help unite and inspire a liberal, moral community of opposition. His playing the song at Mississippi voting rallies demonstrates the strength of his commitment. His singing of the song at the March on Washington where Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech solidifies his status as a progressive icon. Listening to the song today, one is both struck by Dylan’s piercing sense of observation and the sheer guts of his determination to tell the truth.

Once again, it is what Bob Dylan is demonstrating what he is here that will make who he becomes down the road such a powerful and necessary challenge.

7. "Boots of Spanish Leather" - Dylan returns to the personal plane for what is probably the most beautiful and emotionally moving song on the album. Based upon his own "Girl from the North Country" (which was based on the British ballad "Scarborough Fair"), Dylan softly fingerpicks his guitar, while his voice floats sorrowfully as a ghost. The first verses of the song take turns between two lovers. One, a female, is traveling on a ship to Spain, leaving the other behind. She continually asks what she can send back to him, while the heartsick lover repeatedly insists that he only wants her quick and safe return. When a letter finally arrives saying she doesn’t know when she will return, the lover, his heart crushed, requests the material gift of the title. The sad acceptance of the finality of all his hopes and dreams gives the ending a simple and elegant and profound closure that simply breaks the heart. This one is a classic.

8. "When the Ship Comes In" - This is a rousing song that promises revenge for those on the shoreline for some unnamed crimes. The song is obviously inspired by "Pirate Jenny" from Brecht and Weil’s Threepenny Opera, but Dylan does not write himself in as a personal participant or state any emotional satisfaction. Instead, the song seems designed to function as a generic folk song that promises reprisal for repression or injustice. There are eight verses, and each one has lovely verbal images, but the ultimate result of the tune is a more perfunctory statement than the other, more powerful songs on the album, and basically, it just sails by.

9. "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" - This is my favorite song on the album. After more than 50 years since the incident dissected in the lyrics, Dylan’s slow, dispassionate depiction of the killing of a 51-year-old African-American barmaid at a hotel in Baltimore by the hand of a drunken young son of a wealthy tobacco family still brings shivers. Here, Dylan crafts another classic ballad in the mould of ancient tales of murder and injustice from material ripped right from a daily newspaper, demonstrating the extraordinary power that could be had from simply reporting the current conditions he sees around him. But the heart of the song is its human content. It is Dylan’s simple but complete depiction of the humanity of its victim that brings the tale its extraordinary power and pain. Hattie Carroll is not just a name in a news story, she is a fully fleshed out human being, and Dylan takes his time for us to get to know her. We know she was 51 years old, the mother of ten children. We know she worked hard at a thankless, dirty job. She cleaned up the food and emptied the ashtrays. Her death is "lonesome" because before she was killed she was invisible, a nobody to the wealthy white patrons she served silently every night. We picture a hard life of drudgery to support her family, to which nobody ever gives a thought. And the idea that a 24-year-old William Zanzinger could simply walk in and beat her to death with a cane simply because "he just happened to be feeling that way without warnin’" is shocking enough, displaying as it does the sickening myopia that allows one not to recognize another person as a fellow human being. But that’s not the real pain of the story. After four long verses, filled with detailed descriptions that paint the entire picture so vividly that we feel we were there and knew everyone deeply, Dylan drops the bomb. After his trial in the hallowed halls of the courts of Maryland, Zanzinger receives a six-month sentence. Dylan’s simple reporting of the fact jabs a knife right through our guts.

And you who philosophize disgrace and criticize all fears,

Bury the rag deep in your face, for now’s the time for your tears.

"Hattie Carroll" has a haunting melody which suggests eternal loss - both of humanity and of innocence, and it’s a tune that intensifies when Dylan plays it so softly and mournfully. If poor Hattie Carroll deserved nothing else in this life, she at least deserved this memorial, and Dylan takes his time to slowly give her everything he can.

And sadly enough, in the end, we realize that the greater tragedy is the countless millions of other innocents who never had a song sung or a word said over their bodies. This song is for them, too.

10. "Restless Farewell" - After a full album’s worth of prophecies, careful observations and heartbreaking truths, Dylan appears at the end, ready to move down the road. Something is always pulling at him, calling him away. Despite his multi-stated need to move on, he sounds weary, his voice hollow and sad, as if he’s giving himself away, saying instead that he needs to linger just a little more time with all that he’s said. The guitar is picked slowly, hesitatingly, with no real drive to the song. Yet he knows that has to move on. In a sense, this final song is the most revealing of the Bob Dylan that we will all come to know. By another year and a half, this man that we think we know will be transformed all out of recognition, pushed by a relentless muse that will take him places no popular artist had ever ventured before. But we have this album still, and at this snapshot at the beginning of 1964, we will always have the 22-year-old protest folksinger he so briefly and perfectly embodied. Dylan won’t care, though. As the last line on the album proclaims, "(I’ll) bid farewell and not give a damn."

Personnel:

Bob Dylan - vocals, acoustic guitar, harmonica

The Rolling Stones:

The Rolling Stones (EP)

(UK: January 17, 1964)

The EP - or "Extended Play" format - was much more popular in Britain than in the United States during the 1960s. Basically, they were a halfway house between a 45" single and the 12" LP (Long Playing) album. EP’s were the same size as singles, but they could hold more music: about 7:30 per side. Often, when a group like the Beatles, released an album, the record company would release EPs, usually containing four songs, so they could sell them to kids who couldn’t afford the entire LP, or only wanted a few of the songs. Occasionally, as with this EP, they would be comprised of new material that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

The Rolling Stones had released their first two singles in Britain in 1963: "Come On" backed with "I Want to Be Loved," and the Lennon-McCartney-composed "I Wanna Be Your Man," backed with an original called "Stoned." The latter had reached the Top 20 in the English charts, and while Decca, the Stones’ record company had their hungry eyes on the Beatles and their mounting millions of sales, this group was a little different. The Rolling Stones, though a rock ‘n’ roll group, were more based the blues and black R&B than the Beatles. And there was something else about them, too - they were a little, well . . . dirtier.

Not ready to take a risk with an LP yet, Decca decided to start the new year off with an inexpensive EP of new Rolling Stones recordings. It worked - the release hit the No. 1 spot on the British EP chart, giving the record company the confidence to go ahead with a full Stones album in the early spring.

Unfortunately, for American fans, however, most of these songs were not heard in the U.S. "You Better Move On" appeared on the 1965 American album December’s Children (and Everyone’s). "Bye Bye Johnny" and the Stones’ version of "Money" would not appear in the States until the release of 1972’s compilation More Hot Rocks (Big Hits and Fazed Cookies). "Poison Ivy" wouldn’t show up stateside until 2002!

Finally, in 2004, the EP would finally be released in America in its original form as part of a box set entitled Singles 1963-1965. While I wouldn’t purchase that whole set just to hear the EP, the four songs can be purchased individually, and the whole set can be found on Spotify.

Thousands of British youth, on the other hand, suddenly got hip to the fact that there was a serious challenger to the Beatles out there, and they meant to be taken seriously. There wasn’t anything cute about them, and they weren’t taking prisoners. This is punk rock, circa 1964. One can only imagine how tough this sounded in England at the time.

SIDE ONE

1. "Bye Bye Johnny" (Chuck Berry) - The second of many Chuck Berry covers by the Stones, "Bye Bye Johnny" blows away the "Come On" of the group’s first single. Gone is any tightness or nervousness. The band just up and roars, while Jagger spits out the lyrics confidently, full of sass. Keith Richards plays with such fluidity that he could be Chuck Berry (or at least his illegitimate son). Bill Wyman’s bass pumps so solid, and all-in-all the sound is so loose and cocky that one just thinks that this has to be the blackest-sounding British record ever cut (at least so far).

2. "Money" (Barry Gordy/Janie Bradford) - This, however, pumps it up a notch. While the Beatles’ version of Gordy’s song was hard, tough and liberating, the Stones’ take on the thing sounds like they’re out to assault you. This is some dark-sounding shit, with a threateningly LOUD guitar tremolo seemingly recorded in a back alley. Jagger sounds positively rapacious here, while Brian Jones’ bloozy harp just wails in defiance.

SIDE TWO

3. "You Better Move On" (Arthur Alexander) - This song shows a completely different side of the group, as they demonstrate that they can convincingly convey a pop/soul ballad with real feeling, as well as pop appeal. Arthur Alexander is the man who wrote the blissful "Anna" that John Lennon sang so perfectly on the Beatles’ first album. And while this song isn’t quite in that league, it’s pretty and effective. A strumming acoustic guitar gives it an intimate appeal, while Jagger sounds soulful and absolutely unique.

4. "Poison Ivy" (Jerry Leiber/Mike Stoller) - This is a silly Leiber & Stoller song (which I love), but the Stones do it so LOUD and heavy, that somehow even this fluff comes off like a threat. They sound like the ultimate garage band here (though they’re already too professional for that - Charlie Watts’ deft cymbal crashes let you know they’re fully in charge.)

Personnel

The Rolling Stones

Mick Jagger - lead vocals, tambourine

Brian Jones - guitar, backing vocals, harmonica, percussion

Keith Richards - guitar, backing vocals

Charlie Watts - drums

Bill Wyman - bass guitar, backing vocals

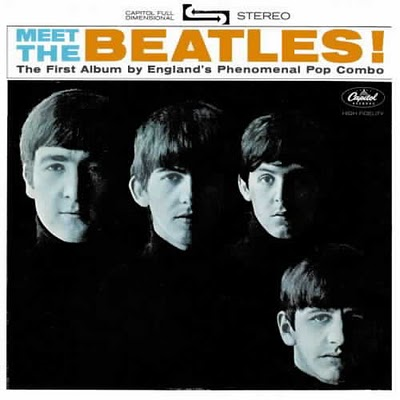

The Beatles: Meet the Beatles!

(US: January 20, 1964)

Here it was at last! This was the album that started the cultural revolution in America going with an unbelievably loud and definitive crack. This music is so thoroughly engrained in our collective consciousness, it’s so much a part of our very bones and blood, that it’s impossible to imagine today just how miraculously revelatory, rich, beautiful and overwhelming it was at the time. Everybody had it. Everybody played it. Over and over and over again. And it just kept getting better!

Capitol’s strategy was a sound one, I suppose, looking back. Since they (temporarily) did not have the rights to the Please Please Me album, they took what they did have - the group’s November 1963 second album, With the Beatles. Instead of releasing it as-is, with its 14 songs, they pulled nine (the eight originals and one cover), stuck the monster-selling "I Want to Hold Your Hand" single up front (along with its B-side, "This Boy," and added the rocking "I Saw Her Standing There" (which they did have for some obscure legal reason. That made 12 solid tracks of heavy Beatlemania, leaving five more tracks (covers all) to make up the bulk of what would become The Beatles’ Second Album. By slicing and dicing and shorting the fans on the number of cuts, single British Beatles albums could be extended and expanded over time and number of releases, Capitol could exponentially multiply their cash cow, and nobody in America would be the wiser (or would really care).

The Beatles themselves did not care for this duplication and duplicity, but from a legal standpoint, there was nothing they could do about it. And from a stance of pure power, they were not able to put their collective feet down until 1967 and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Generally speaking, I consider the original Capitol releases of the Beatles’ records to be of no more of historical interest, as they display to the world just how the group was introduced to the nation. But this first one I make an exception for - it’s truly one of the greatest rock ‘n’ roll albums of all time. Yeah, even better than With the Beatles (though it’s two songs shorter). It’s the only American Beatles album I have on compact disc (excepting of course, Magical Mystery Tour, which is a completely different story.)

First of all, it opens with "I Want to Hold Your Hand," which is so absolutely definitive and revolutionary that it just blows your head off. They follow that with "I Saw Her Standing There," which actually increases the energy, then they momentarily slow things down with the gorgeous "This Boy." From there, bam!, the album jumps right onto the dynamic beginning of With the Beatles, and off we go. Side one ends with all the exhiliration of "All My Loving." By the time you get there, you’ve reached the end of one of the greatest sides of any LP in rock history. Period.

Side two is not quite as consistently intense - how could it be? Side two of With the Beatles was a little less forceful than Side One, there is no single hit, and there’s no climactic "Twist and Shout" or "Money" to wrap everything up. But hell, who cares? (Most people weren’t even bothered by the silly gear-shift of "’Til There Was You," noting instead the group’s versatility and ability to play "pretty music.")

Meet the Beatles! is more than history - it’s a truly great album, a truly great moment - one that you can experience over and over again. If it is not canonical Beatles, that is, if it is not truly necessary or essential, it’s damned close. I wouldn’t be without it.

Rolling Stone magazine ranks Meet the Beatles! at No. 59 of their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

All tracks written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, except where noted.

Side One

1. "I Want to Hold Your Hand"

2. "I Saw Her Standing There"

3. "This Boy"

4. "It Won’t Be Long"

5. "All I’ve Got to Do"

6. "All My Loving"

Side Two

7. "Don’t Bother Me" (George Harrison)

8. "Little Child"

9. "Till There Was You" (Meredith Wilson)

10. "Hold Me Tight"

11. "I Wanna Be Your Man"

12. "Not a Second Time"

Personnel

John Lennon - vocals, rhythm guitar, harmonica, organ on "I Wanna Be Your Man"

Paul McCartney - vocals, bass guitar, piano on "Little Child"

George Harrison - vocals, lead guitar

Ringo Starr - vocals, drums, percussion

George Martin - piano on "Not a Second Time"

The Temptations:

"The Way You Do the Things You Do"

(January 23, 1964)

Berry Gordie of Motown Records knew he had a special combination of vocalists in the group he had put together. What they didn’t have, so far at least, were hits. And the group had already released seven singles since signing in 1961. Only one, 1962’s "Dream Come True" had made a dent in Billboard’s R&B chart, reaching No. 22. The rest - nada.

Singer/songwriter/producer Smokey Robinson reportedly played around on the bus with co-Miracle Bobby Rodgers, seeing who could come up with the lamest pick-up lines. They started singing them, and things just fell into place. They decided to give the result to the Temps to see what would happen. The ridiculously infectious, catchy song was recorded, released two weeks later, and before anybody knew it, the Temptations had their first hit.

This song is so simple, but it’s so joyously upbeat, rocking back and forth like a nursery rhyme, and the voices sound great. Eddie Kendricks sings the lead in a dreamy falsetto while the other Temps of the time lock around him in quietly rolling agreement. There’s a slight doo-wop feel, but the song sounds more modern than the 50s arrangements, and that probably has to do with the beat. Producer Smokey gets it right, and he holds off on the horns until the second verse, culminating in a key change and a tenor sax solo that propels it upward in a state of perfect bliss.

"The Way You Do the Things You Do" hit the No. 1 spot on the R&B chart, and even crossed over to make No. 11 on the Billboard Top 100. It’s not only a fun song, it’s historical. The Temptations would go on to be one of the biggest-selling (and multi-talented) male vocal groups, not just of the 1960s, but of all time.

Thanks, Smokey!

Louis Armstrong: "Hello, Dolly!"

January 1964

Nobody saw this coming! Least of all Pops. Right in the middle of the first flush of Beatlemania, 62-year-old jazz legend Louis Armstrong strolled along and - for one week at least - knocked the moptops out clean out of the top spot on the charts.

This wasn’t even supposed to be a hit record. Hello Dolly! was a new Broadway musical opening, starring Carol Channing, and Armstrong had made a demo recording the month before to help promote the show. Something clicked somewhere though.

I never thought that this was such a great song - and neither did Armstrong. But just listen to the man. There is something absolutely irrepressibly loving and celebratory about how America’s greatest musical artist totally wraps his gravelly voice around this piece of fluff. The man could sing anything. And then there was that trumpet solo. By this point in his career, Louis Armstrong could say more in a few notes than any other musician with a horn could say with a thousand.

Yes, this was just one more in a long series of decades of extraordinary performances. The miracle isn’t in the record - actually, the real miracle is the man’s entire life. But it just seems so magically fitting that the greatest musical force of the second half of the century should just so fleetingly be interrupted by the greatest musical force of the first half of that same century. It’s almost as if Pops were saying, "Okay, y’all go and have fun. But don’t forget what I done!" Amazing.

Muddy Waters: Folk Singer

January 1964

Now this album is what I would describe as "kind of bluesy."

Actually, this album is a mother. There’s nobody can sing and play the blues as hard and heavy as Muddy Waters. This extraordinary set was recorded in 1963 as kind of the original "Unplugged" session. Muddy was, of course, the "king" of Chicago electric blues. But he did originally come from the Mississippi Delta, and this record reveals all of his roots in their raw, ragged glory. The idea, I believe, was to transcend Muddy’s limited blues audience in an appeal to the "folk scene" of the early 60s. However stupid the concept, it resulted in a masterpiece. It’s just Muddy on vocals and acoustic (oh, my God, hear that slide!), joined by the inimitable Buddy Guy, Chess master Willie Dixon on bass, and one Clifton James on drums. If you have never heard this, prepare to have your mind blown. The sound alone is staggering: the full presence of Muddy let loose in the studio is so full and rich that it’s just plain scary. I mean, this stuff is just evil.

Track Listing:

1. "My Home Is in the Delta" (Waters)

2. "Long Distance" (Waters)

3. "My Captain" (Dixon)

4. "Good Morning Little School Girl" (Sonny Boy Williamson)

5. "You Gonna Need My Help" (Waters)

6. "Cold Weather Blues" (Waters)

7. "Big Leg Woman" (John Temple)

8. "Country Boy" (Waters)

9. "Feel Like Going Home" (Waters)

Personnel

Muddy Waters - Composer, guitar, vocals

Buddy Guy - Guitar

Willie Dixon - Bass

Clifton James - Drums

CD BONUS CUTS

10. "The Same Thing" (Dixon)

11. "You Can’t Lose What You Never Had" (Waters)

12. "My John the Conqueror Root" (Dixon)

13. "Short Dress Woman" (John T. Brown)

14. "Put Me in Your Lay Away" (L.J. Welch)

The CD version of the album also features five contemporary "electric" tracks from Muddy and his band. So if you didn’t have a point of reference before, you do now. Just awesome!

COMING SOON:

1974 in Music: January

1984 in Music: January

1994 in Music: January

2004 in Music: January

2004 in Music: January

1954 in Music

1964 in Music: February

send submissions to:

peteywest@yahoo.com

peteywest@yahoo.com

- petey

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment