And whatever you may think of them, you’ve got to admit that this is pretty amazing. Looking back over what the unprecedented 50-plus years’ body of work that this group has managed to produce, there’s no question that it is a colossal and mind-boggling achievement, an unparalleled accomplishment of sheer length, breadth, depth, longevity and tenacity.

Critical discography rationale and theory

Why am I doing this? First of all, I enjoy making discographies - I’ve done it since I was a kid, and I thought, what the hell, why not? And I have definitely been having fun with the project. Even someone who has been a fan of the group for so many decades can be surprised with all the material that has hitherto gone unnoticed or at least under-scrutinized. To say the least, I’ve uncovered a lot of surprises.

Peculiarities of rating the Stones

First of all, since my primary interest (as far as critical rating goes) is to form what can be seen as a widely accepted critical canon with broad agreement and appeal, I have chosen to adopt the four-star rating as a general critical standard. When I give a particular work four stars, what I am saying, is that this particular artifact (in this case albums - I do not rate singles) has demonstrated a level of quality and relevance to be considered a canonical part of the cultural tradition in which it participates. (In other words, it is an "excellent" rating). To demonstrate, right off the bat, how broadly I use this rating as a critical paint brush, let me go ahead and confess my decision to grant every Rolling Stones studio album with a four-star rating or better. Why? Simply because they are the Rolling Stones, they are one of the greatest and most important groups in popular music history, and though some work is clearly superior to others, they have maintained a consistent level of quality throughout their long career. I simply do not see any original Rolling Stones album that I can say, without question, measures any less.Now, you may feel free to disagree with me. Some people, I am aware, think that some (even a good many) of their albums are garbage. Fine. Taste is relative. And there are certainly some albums that I rate at four stars that I believe are clearly much more personally preferable to others. But I’m not going to become didactic about it. There is simply too much room for personal variance in reaction and judgment to begin any kind of argument that I would consider profitable on any level. While I would definitely hold an unusually creative oddball gem like Between the Buttons several leagues higher in my own estimation than a comparatively dull, late-career effort like Bridges to Babylon, the fact remains that both of these albums are nearly equivalent in their critical/historical ramifications: that is, they are both top-notch, professional collections of then-new music by one of the greatest bands on the planet. Unlike many other popular artists, I do not consider the Stones to have made any "below industry standard" material, unlike many of their peers (Bob Dylan, the Who, the solo Beatles, etc.). There are no titles (I think) that I would find myself debating whether or not I would want to have in my collection, no matter how much more I would prefer one over another. In short: I believe that all the Rolling Stones’ original studio albums are equally canonical. Now, while that doesn’t mean that I think you should own them all, it does mean that if you did, I would consider you to have a pretty great Rolling Stones collection.

Still, most of us will have to pick and choose. This is especially true for the first several years of the groups’ career, when - like the Beatles and others - the UK and US releases differed significantly and produced a great deal of overlap. Decisions should be made here, and I will definitely be addressing this topic.

Moving on to the question of live albums, however, I absolutely do not see anywhere near the same level of quality, consistency and essentialism in this wide section of the group’s catalog that I do in their studio recordings. Why this is, I cannot say, but I can at least note a good deal of redundancy. It is a bit puzzling to me, as well, since - as anybody who has seen the group live can tell you - they are one of the greatest live rock bands on the planet. Why then do they have so many mediocre live albums? (There is only one of the entire lot that I would grant four stars - though I would give none of them less than three.) Is it one of those cases of "you had to be there?" where the true excitement of the performance is essentially lost in the process of recording? Or can it be that whoever makes these selections for release has consistently bad judgment? I honestly don’t know.

Once again, some degree of subjectivity enters into this question as well - some fans may find some of these live albums as absolutely magnificent, the brightest blossom of the band's sound. Common consensus says no, however, and my ear concurs. Too often the Stones sound fat and flabby on concert discs, though occasionally they "catch fire." Of course, I could just be jaded, being unfairly influenced by the attitude of "here we go again" when I listen to these discs. Still, I don’t find it worth arguing about, and with the exception of 1970s astonishing ‘Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!’, I do not find any Stones live albums essential, and therefore canonical. I consider them, rather, as "auxiliary" pieces to the center of their collection and I advise as such. All those who disagree with me should certainly feel free to hear it their own way.

Finally, we have the question of compilation albums - the number of which this group has is literally astonishing. I can’t think of anyone this side of Elvis to have more repackages to their credit. And since almost all of these albums contain extraordinary music, it’s a little difficult to dismiss any of them out of hand. But nobody (except a compulsive collector) is going to want or need all these titles. So the question becomes: which compilations are most definitive in representing the band as defined over different parameters of time, sense and sensibility?

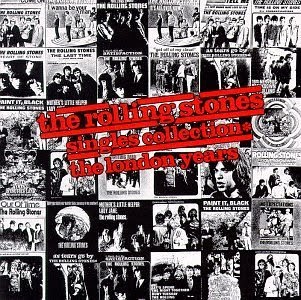

While we will go over each of the major compilations as they arise, I’m going to address them directly as we start out, as how one chooses to view the group’s history is going to be determined by all sorts of personal considerations, as well as the actual facts of the band’s recording history. Just note, however, that I do not give more that four stars to any Rolling Stones compilation. And the basic reason for that is that I find that none of them are unconditionally perfect for every collector. Now, on a personal level, while I find 1989’s 3-disc set Singles Collection: The London Years to be worth as many stars in the firmament, and I would never want to be without it, I cannot say that every Stones fan needs every single A-side and B-side from 1963 to 1971. For many people, this would just be overkill. So, while I still consider it (and pronounce it) the best purchase possible, I can’t unconditionally say it’s for everybody.

Okay, now that I’ve got that preliminary junk out of the way, just what do my star ratings mean?

My rating system

««««« - Five stars indicates a work which is not only universally regarded as canonical, but has established its place in our culture (with my blessing) as one of the finest representatives of its particular style of art available. I do not give five-star ratings often or lightly, and when I do, I mean to say that this album possesses such value that it should be regarded as essential for any person who is collecting musical popular music. These are the touchstones around which our musical world is built, they are the essence of the canon, and they should be in every serious collector’s possession. Ignorance of these titles can legitimately be argued to be a serious lapse in one’s total educational and cultural profile. The must be purchased and fully absorbed for one to be a total civilized human being. (To quantify it to some degree, I would say that these are roughly considered the 100 greatest popular music albums of all time.)«««« - The four-star rating is the one you will find most often in my discographical system. The reason is simple. It indicates that the album in question is good or historically significant enough to have earned a place in the Popular Music Canon through the "critical mass of consensus", as well as my (sometimes reticent) approval. These are "excellent" albums, though not every person might think so. If one does not particularly care for a given artist or genre, for example, such a designation is really rather meaningless to them. But these are albums that I believe, have demonstrated their value and vitality - often over a long time - to critics and fans and are well deserving of at least a listen. Likewise, if one is an enthusiast or fan of some critically neglected artist, one would argue that their ratings should be inflated. What can you do? I’m doing the best I can here. (Quantitatively speaking, I would say that this rating would roughly apply to the greatest 1000 popular albums ever.) Obviously, the ultimate goal of life is to collect all the 5-star and 4-star albums that exist, along with the 3-star albums from your favorite neglected, under-appreciated artists.

««« - Three stars for me might mean five stars for you. This rating is reserved for basically two categories of albums: 1) Works that are generally considered to be substandard for a particular artist of worth. These could be highly valued by devoted fans of some particular artists; 2) The average work of average talents. They neither inspire nor disgust. They line the walls at the entrance to Dante’s hell, though they do not play inside. (Once again, if this is an artist that is particularly resonant to some individual - or perhaps even a large number of individuals - who am I to say that they are wrong?) These albums simply do not have the "critical mass of consensus" needed to be considered canonical. I do not look down on them - I think of them as "adjuncts".

«« - If there are only two stars given to an album, something really went wrong somewhere. Either I cannot escape the fact that this is purely mediocre crap, or the album’s concept was in some way so flawed of ill-conceived that it is difficult to fathom. Still, there may be those who find a special fascination with it or perhaps require it for a "completist" purpose. You won’t find me giving many of these.

« - I don’t give one-star ratings. If I consider something that is this negligible, I am most likely going to simply ignore it. There is plenty of pure crap out there, and I don’t see any reason wasting my time (or anybody else’s) in even addressing it. I know that some crap is very popular, but that doesn’t make it less crappy. (And by crappy, I generally mean trite, formulaic, cookie-cutter product that is simply designed to sell to the non-musical individual for the sake of tastelessly ornamenting their drab lifestyles.) I’m sorry, folks. I believe in subjectivity and personal taste, but we have to draw a line somewhere.

On certain occasions, I will not give a rating at all. This does not mean the album is worthless. It might, even perhaps, be a stellar addition to someone’s collection. The absence of a rating or score simply indicates that there are multiple conceptual hurdles that this package presents that I do not feel I can give an adequate, overall assessment that would provide anything close to a universal consensus. These are quirky, oddball albums. Just read what I have to say and make up your own mind.

Collecting the Rolling Stones

Building a comprehensive, satisfying Rolling Stones collection is nothing if not challenging. And constructing anything close to what might be called "definitive" is well-nigh impossible without falling nearly into a "completism" that is constructed of the worst kind of massively jerry-rigged corporate sinkholes concocted (accidently or otherwise) for any major artist on this side of Elvis.There are quite a number of reasons for this situation, most of which will become obvious as we travel through this collector’s guide, but fortunately, there are some well-trodden pathways that can lead you right to the heart and core of the group and its best, most significant work. If you trust me, hang on and pay close attention, I promise that I can show you the best strategies for approaching this group’s enormous, convoluted catalog. I can scout out the way for you, and make my best recommendations. However, it is you that will ultimately have to make the final decisions for the approach that is most appropriate for you.

Basic strategy

Now, there are many fans (or aspiring fans) who would like to approach the group’s entire work chronologically, which is only a natural thing to do, especially for those who are prone to the pleasures of discographical history. And I will show you the various options for doing so, along with the inherent complications involved. But the history and variety of the Rolling Stones’ output (and packaging) covering a period of more than 50 years, makes me recommend a different path, particularly for beginners (or near-beginners), and there are some very good reasons for this:l The Rolling Stones’ musical output is, undeniably, and particularly when personal taste and time preferences are factored in, considered to some degree variable. Only their most rabid supporters are going to want to consider collecting anything approaching their entire catalog - especially as difficult as that is.

l However - There is a widely recognized consensus as to the core of what is considered their best, and most essential work, at least in album formats. And it is in this area that I recommend that most (if not all) collectors begin.

l On the other hand - The Rolling Stones are one of the greatest "singles artists," not only of the 1960s, where so many artists made some of their most profound statements, but indeed, of all time! Not only are there such a large number of individual songs from this period that I would consider absolutely essential for any proper music collection, but indeed, this is one group who would continue to consistently produce high points, well along into the later years of an increasingly more erratic career. So, in order to provide a proper balance for their unquestionably classic albums, no Rolling Stones collection is going to be in any way acceptable without resort to some kind of compilation - and in my view, it should probably be more than one. But, as we shall see, there are so very many ways that the Stones are collected and compiled, that choosing between them is a very careful craft, taking into account factual content, historical significance, as well as private taste. Make no mistake about it - decisions must be made!

l Finally, it should be pointed out, that the Rolling Stones have one of the largest selections of live recordings to choose from (well, not from a Grateful Dead fan’s point of view) of any major rock group. There are (mostly) widely varying assessments of many of these albums’ quality, historical necessity (and thus canonicity) of many of these collections. There is also the question of whether they should be considered along with the other Rolling Stones albums, or should they be seen as an auxiliary sub-genre in themselves? We will leave this question open for the individual to decide, while approaching them in both manners and contexts. (I have already clearly given what I believe should be considered the lower-level ranking of their relative status.)

Now, of course, the considerations listed above are only in play for those of us who insist on having hard-copy collectibles in our actual possession, and at this point in time, that means compact discs. (Those who are of the neo-vinyl persuasion, I would only recommend a handful of the Stones’ greatest albums for this sort of pricey purchase.) If, however, an individual is satisfied with a purely digital collection, then acquiring the Stones song by song can make the entire enterprise vastly easier in many respects.

However - I must sternly warn everyone (as indeed I will do in regards to every significant albums artists) that part of the Rolling Stones’ recorded glory consists in their magnificent, holistic, conceptualized wonder of their albums as they were originally intended and released. I may be sounding picky and old-fashioned here, but a great many albums of the album age gain much of their brilliance do to their particular organization as well as their content, and they cannot be truly appreciated and enjoyed in part and partial any more than a great novel or a film can, and moreover respect should be shown for the artists’ intent.

So, with all those little insights and caveats in mind, I think we should feel free to proceed.

The great Rolling Stones albums

As I intimated before, one can start here or one can start with singles, but sooner or later, these magnificent specimens are going to come heavily into play, so we might as well get started with them right away.To begin with, there is almost universal consensus that the Rolling Stones reached an extraordinary height of maturity, combined with a dialectic that resonated as strongly with their own time and cultural context, in the period of 1968-1972. During this time, they produced four consecutive studio albums that are as highly regarded as anything ever produced in the rock era. I submit that these four albums are the absolute core, not only of every Rolling Stones collection, but also represent a very significant part of the core of any modern music collection, period. It is my recommendation, therefore that these four albums be purchased first by any serious music fan:

Beggars Banquet (1968)«««««

Let It Bleed (1969)«««««

Sticky Fingers (1971)«««««

Exile on Main St. (1972)«««««

These are unquestionably great albums, and they represent the absolute height of the Rolling Stones’ mature artistry. They should be owned and listened to intently by everybody. And I should also point out that they gain in perspective and power by listening to them chronologically, as the group’s artistic vision expands to its fullest and most beautiful and grandiose expression on their 1972 masterpiece, which all the sane world regards as "the greatest rock ‘n’ roll album of all time." These four albums should not only form the core of one’s Rolling Stones collection, but also one’s listening. In the largest sense, everything else the group has ever done - before, since, or between - only finds its ultimately appropriate resonance in relationship to these four staggering individual statements of purpose. (Of course, we shall discuss each album individually, once we make our way through the entire chronological catalog.)

In addition to - please note the term "addition" - to these four milestones, I would unhesitatingly add two more Rolling Stones albums to the list of "absolutely essential," though they both come from remarkably different time periods and display quite distinct sounds and perspectives.

Aftermath (UK, 1966)«««««

Some Girls (1978)«««««

Once again, we will discuss the particulars of these two albums in the chronology section. But let me point out, first of all, that the first title - Aftermath - is, among may of the early Stones’ albums - available in two completely distinct configurations. There is the original UK-released album designed with its own brilliant conception and flawless execution. And there still exists a quite-interesting, but definitely inferior U.S. version that has different artwork, and - more importantly - different tracks and running orders. Be sure to purchase the original UK album.

Some Girls, fortunately hails from a different era where continuity of an album had long been ceded as a given even by the corporations who distributed them for profit. Taken together, however, with the addition of these two gems to the core group above, you will definitely have the best of the Rolling Stones LPs. (In short, Aftermath is their first great album-length statement and a perfect expression of its era, while Some Girls is the later-in-life stunning comeback record that re-assured their immortality.)

We will return to look at the merely excellent Rolling Stones albums shortly, but it is my firm belief that after all these six albums have been acquired, it is definitely time to turn to the collection of singles, something this group is more than well-noted for.

The best compilations of singles

When it comes to compilation albums, the Stones offer more selections, flavors and sizes than any group on earth. Where does one begin? Well, while I have some very strong opinions on that regard, the final decision must come down to the one who is doing the collecting. So, for that individual, I here present what I argue to be the very best Rolling Stones compilations, and will present my arguments, pro and con, for each one:

Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass) (US, 1966)««««

This first selection was the very first compilation of Rolling Stones hit singles, and it not only packs a historical punch with its astonishing concentration of power, but it really and truly does feature virtually all of the Rolling Stones’ great early songs. Big Hits is the music that defined the Stones early on, and it can hold its own very well today. It contains only songs that predate Aftermath, and there will be (no doubt) a class of collector for whom this single-disc collection will suffice to represent the early years of the group. Let us not forget that, even if there is no unqualified Rolling Stone LP masterwork before Aftermath, that "The Last Time," "(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction", "Get Off of My Cloud", and "19th Nervous Breakdown" (among others) are absolutely essential for any serious music collection. This album can easily stand by itself even if one does eventually purchase the individual albums from this period - it is a near-perfect stand-alone portrait of the early Stones. (There is a UK configuration of this title from the same year, which I consider less preferable, but I do not think it is even available on CD.)

Hot Rocks 1964-1971 (US, 1971)««««

The second selection is a different kettle of fish. Released only in the United States at the end of 1971, Hot Rocks provided a two-record chronological summation of the band that displayed their growth from snotty upstarts to absolute masters in a magnificent, effortless flow. This is still an excellent representation of their early years, while adding three post-Aftermath essentials ("Paint It, Black", "Ruby Tuesday", "Let’s Spend the Night Together") and two "classic-era" must-have singles ("Jumpin’ Jack Flash", Honky Tonk Women"). There is some overlap with selections from the core albums, but a "live" version of "Midnight Rambler" (from "Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!") makes up for that. All stated, this is probably a much more valuable collection than Big Hits, all things considered. (A second edition, More Hot Rocks (1972) is not nearly as vital and interesting.)

(Another alternative is to supplement Big Hits with Through the Past, Darkly (Big Hits, Vol. 2) (1969), which has the latter singles - among some others - to flesh out the entire 1960s. Personally, however, I would rather have Hot Rocks and Big Hits both, since they are each so complete and beautiful unto themselves.)

Singles Collection: The London Years (1989)««««

Now we come to the third selection. For my money, the 3-disc collection The Singles Collection is the absolute ideal - and the one Stones compilation that I would not want to be without. (But I will admit to being an obsessive.) This set has nothing less than every single released by the Rolling Stones from 1963 to 1971, either in the U.K. or the U.S., including every B-side! Now, I realize that not everyone will want every B-side, especially if they are buying albums from the ‘60s, but I argue that no other collection gives such a comprehensive overview of the band during this period. Plus, everything is arranged chronologically, and listening to the entire story unfold over time is absolutely astounding. From my perspective, if one has The Singles Collection, along with the six great albums listed above, one will have what amounts to something close to an essential Stones collection. There - that’s what I think!Forty Licks (2002)««««

Now, that brings us to our fourth selection, which is the most recent, and certainly the most popular compilation in the Rolling Stones catalog. 40 Licks is unique in that it is the first Stones compilation to include material both from their classic 60s period on Decca and the hits from the older, longer, classic-rock period as well. And, the eras are separated on two different discs. Now, it is obvious to me at least, that the singles from the first era are more significant, but looking at the contents on disc 2, I have to concede that such songs as "Start Me Up," "Angie", "You Got Me Rocking", "Mixed Emotions", "Undercover of the Night", and "It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll (But I Like It)" are, arguably essential or at least near-essential as well. (Don’t worry about the songs from Sticky Fingers, Exile on Main St. and Some Girls - you’ve got those albums!) And isn’t the entire second disc such a beautiful portrait of the band from the 70s on? Why one could almost argue that it is the one essential later-Rolling Stones disc. (Plus, it’s got four songs you won’t find anywhere else.)

Yeah, but look at disc one. It’s got 20 undeniably great 60s Stones hits - all essential. But it’s not in chronological order! For some reason, this doesn’t seem to bother some people. And if you are one of them, then just go ahead. When I listen to a compilation, however, I like (or rather, need) to get a sense of the flow of history. So while 40 Licks just may be the perfect collection in terms of the songs you get, I find it terribly irritating to listen to. Now, of course, in this golden digital age, one could simply recombine all the tracks in their proper chronological order on his or her computer or I-Pad. But if you’re going to do that, why not just purchase all of your Stones songs separately and arrange them just they way they should be? (Well, at the conclusion of this entire discography, I will lay out my pattern as to precisely how to do just that for the entire Rolling Stones collection! But, we’ve still got a lot of material to work through first.)

Looking at disc 2 of 40 Licks, I see what looks like to me, the best, or most definitive post-60s Rolling Stones collection available. The only other one I would even consider is:

Jump Back: The Best of the Rolling Stones (UK, 1993/US, 2004)«««

This has 18 choice hits - but remember, you already have seven of them if you’ve got the essential albums listed above. So, I would go with the 40 Licks package, like most people seem to do. (Of course, if you want to go "whole hog," you could always get Singles 1971-2006 (2011), which features every single - A-side and B-side - that the Stones released in that period. All on 45 mini compact discs! Do not do that unless you’re as insane as I am.

Do you see how difficult it is to put together the perfect Rolling Stones compilation, even after you’ve sorted out the essential albums? (It’s going to get even rougher when we start to go through the 1960s albums, so hold on.) I think there’s an excellent argument for buying any of the four compilations listed above, or any combination. (I have all four of them, and they each serve a different purpose and effect - but that’s me.)

All in all, one must choose what one believes is right for one’s own particular needs. And of course, the perfect Rolling Stones single compilation can be had simply by purchasing every Stones single separately on download. ‘Nuff said?

.jpg)